Harper Self, UF Class of 2023, Holocaust Studies Certificate, discusses her research on Spain and Greece’s Jews under the Nazis.

The Meaning of Citizenship: Spain and the Sephardic Jews of Salonika During the Holocaust

The 1492 Edict of Expulsion created by Queen Isabella of Castile and King Ferdinand of Aragon, epitomized religious intolerance, forcing Jews and Muslims to convert or leave Spain. In 2015, the Spanish government, as a form of reparations, offered citizenship to those who could prove their Spanish Sephardic ancestry. Three thousand people who applied were rejected, while 17,000 still await notice. The government stopped taking applications altogether in 2019. It is unclear why so many applicants were rejected. But this is not the first time the Spanish Foreign Ministry has offered citizenship to Sephardim abroad. In the 1920s, Sephardic Jews descended from expellees from Spain were also eligible for Spanish citizenship. The largest of these communities was in Greece, in the port city of Salonika.

My research concerns citizenship and the Spanish Sephardic Jewish community of Salonika following the German occupation of Greece in 1941, and the subsequent threat of deportation to Auschwitz-Birkenau between 1943 and 1944. What is citizenship? We think that it includes protection by one’s government, but does that necessarily mean housing them within its borders? I argue that the rescue of the Spanish Sephardic community of Salonika was not in fact a repatriation as the community merely stopped in Spain as a way station having been deported to French Morocco four months after they arrived. With the help of the Bridget Phillips Scholarship from the department of history and the Raymond and Bessie Proctor Scholarship from the Bud Shorstein Center for Jewish Studies, I was able to visit the Spanish state archive outside of Madrid where I analyzed diplomatic correspondence. I also studied survivor testimony housed at the University of Southern California Shoah Foundation, which is now accessible through the Isser and Rae Price Library of Judaica at UF. Though I do not have space to present the entire thesis here, I can share a few examples of compelling survivor testimony in addition to a few letters between the three men who aided the rescue effort.

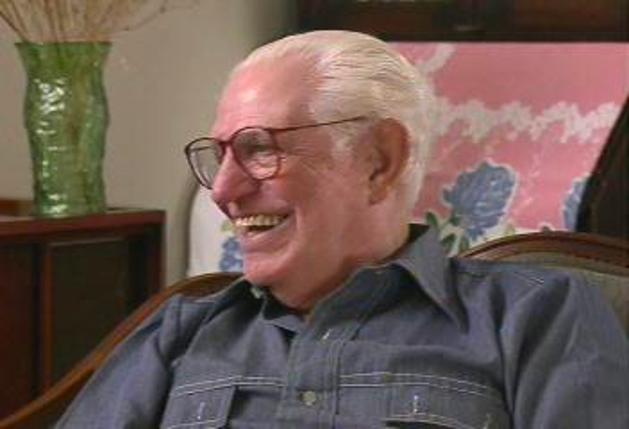

Isac Gattegno (right) was born in Salonika on March 1, 1911. He recounted in his 1996 interview with the Shoah Foundation that when Spanish Sephardim in Greece turned eighteen, they were allowed to choose. They could keep their Spanish nationality and apply for a passport. If they surrendered their Spanish nationality, Sephardim became Greek citizens, forced to apply for Greek passports. Gattegno recounted that his decision was a simple one. Greek males were being drafted into the army. Spanish Sephardim were spared. “I stayed Spanish,” he remembered, “and that is what saved my life.” But Gattegno’s sister, Ema Torres, married a Greek, which nullified her Spanish nationality and passport. Her husband refused to divorce her, which would have given her the right to restore her passport. Without this passport, Ema Torres and her infant son were rounded up and sent to Auschwitz where they later died.

This harrowing story reveals the life and death pressures in Salonika at the time of daily deportations. Within five months after March 1943, 45,891 Jews from Salonika were deported to Auschwitz. Of those, 37,387 or 81%, were gassed upon arrival. The majority of the remainder died in forced labor. Ema’s story shows how important national categorization and documents were to the Germans. She did not differ from her brother Isac or the rest of her community in any way except for her lack of a Spanish passport due to her choice of marriage partner.

Renée Molho, another survivor, remembered the immense stress plaguing those without Spanish passports in Salonika’s Baron Hirsch ghetto. She recounted that though they lived in fear of the deportations, she felt a sense of protection as a Spanish citizen. A few days after the death of her mother, who died of negligence in the ghetto’s makeshift overcrowded hospital, Renée’s father married her Aunt Rachel so that she could also be protected and apply for a Spanish passport. This marriage highlights the desperation of those in the ghetto to grasp some form of reassurance. It also demonstrates how Spanish citizenship could be acquired through marriage. If a man was Spanish, his wife could apply for a passport, however, as seen in the case of Isac Gattegno’s sister Ema, marriage to a Greek man stripped a woman of her ability to apply.

I also studied the correspondence between the three major decision makers: the heroically adamant Spanish consul to Athens, Sebastian de Romero Radigales (left), the antisemitic Spanish Ambassador to Berlin, Gines Vidal, and the reluctant Spanish Foreign Minister, Francisco Gomez Jordana. The Nazis denied Radigales’s request for a collective community passport for Sephardic Jews in Greece on June 17, 1943. Vidal never pressed the question of repatriation. Jordana echoed Vidal’s sentiment. “Diplomats,” he said, “must remain passive, abstaining from all personal initiative.” Both men, Jordana and Vidal, were obstacles to the rescue of the Spanish Sephardim in their reluctance to pressure the Germans for more time to formulate a plan.

Radigales worked tirelessly from his first few days on the job as consul general in Athens to help acquire additional passports for as many Spanish Sephardim as possible. When it became clear the process of rescue was moving much too slowly, Radigales began negotiations with the Spanish Foreign Ministry and German representatives in Greece to rescue the community, proposing everything from Italian trains to passage by boat. Radigales wrote particularly about the need to rescue women, children and the elderly in his letters.

Eventually the community was sent to a concentration camp. Bergen-Belsen is often seen as the camp that in 1945 became the relocated site of Auschwitz prisoners in the final months of the war after being forced marched. It is the camp where Anne Frank died of typhus fever after one such death march. It had not achieved such infamy in 1943, however. Heinrich Himmler, the head of the German police and the SS built a detention and exchange camp there for the holding of Jews with Allied or neutral nationality for exchange with German nationals captured by the Allies. When the Spanish Sephardim from Salonika arrived, they were forced to wear camp uniforms.

Isac Revah remembers that they were treated less cruelly, separated from the rest of the camp, but the motive behind this was more for the German benefit than the wellbeing of the Jews. The Germans, he said, feared the exchange of Jews who appeared inhumanely treated would tip off neutral or Allied regions about the violent crimes against humanity occurring at the hands of the Nazis. Srill, conditions of the migration and living in cramped barracks in Bergen-Belsen were not desirable by any means. Survivor testimony reveals the constant state of anxiety that plagued the community while the Spanish Foreign Ministry worked slowly to plan the transport of the group from Germany to the border station in Port Bou, Spain.

The transport of the group from Bergen-Belsen to Port Bou was a long process. Jordana and Vidal argued about the details. The community was divided into two groups for the transport. Isaac Revah revealed that many families were in distress about the division of the community. Families from the second group feared the Germans would reconsider the decision to repatriate them. Both groups eventually arrived in Port Bou in February 1944. Isac Gattegno remembered being offered oranges by volunteers, the first food he had eaten since the rations ran out on his train car. Spain felt to the several hundred survivors like a safe haven with ample food, allowances, and clothes provided by American aid organizations.

Four months later the community was deported to French Morocco, unable to establish themselves in the country they held legal citizenship. Forced into boats in the south of Spain and after traversing waters under the threat of German U-Boats, the community found refuge at a United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration camp near Casablanca. Isac Gattegno stated upon later reflection, “We left the nice life in Spain to live in tents in Casablanca.”

The experiences of the Spanish Sephardim from Salonika in their search for home are worth sharing because of what we can learn about the politics of neutral countries and redefining citizenship. Each testimony is different and the Spanish Sephardim of Salonika with passports had a much different experience surviving the Holocaust than those without. One survivor from the community Elias Recanati said, “I’m sure there are a million other stories with a million varieties of how the miracle of being saved happened, really, because it’s in a way a miracle.”

So what is citizenship? Despite Radigles swimming against the tide, this example I explored with Spain shows the effort to protect legal citizens was ambivalent at best. There was no room according to the Foreign Ministry for 365 Jewish citizens in Spain. This research matters because it has topical implications to modern issues such as persecution, immigration, and reparations. It also challenges contemporary notions of what citizenship means. Historiographically, this project also provides a different focus in Holocaust history by focusing on Sephardic studies. Ashkenazi Jews (Jews of Germanic and central European descent) dominate numerically in terms of Holocaust victims, therefore they deservedly receive much of the focus. Broadening the focus of the field to include Sephardim (Jews of Mediterranean descent) helps to nuance the study of survivor testimony. It is my hope that by conducting my own analysis of primary documents, adding new information gleaned from survivors, a group becoming smaller every day, and exploring new political interpretations regarding Spanish “neutrality” in the Holocaust, the field of study on this story has been nuanced to an English audience. Uncovering new information about these aforementioned topics pertaining to the rescue of a single community, gives new life to Sephardic studies of Holocaust History that must be further studied in the years to come.