By Madison Ferguson

Madison Ferguson is Gary R. Gerson Scholar in the Bud Shorstein Center for Jewish Studies. Her undergraduate research program is being supervised by Professor Natalia Aleksiun.

Over winter break 2024-25, I had the opportunity to travel to New York City to conduct research for my history honors thesis. My research focuses on the codification of bioethics in response to the unethical conduct of medical professionals following World War II.

Key documents, such as the Declaration of Helsinki of 1964 (DoH) and the International Covenant of Civil and Political Rights of 1966 (ICCPR), are essential to my discussion on the role of international bodies in establishing and enforcing ethical standards within the medical community. Consequently, my research led me to the United Nations Archives and the New York Public Library Archives.

This trip was generously funded by the Bud Shorstein Center for Jewish Studies, and in particular due to the support provided by the Gary Gerson Jewish Studies Scholarship Fund. Thanks to this support, I was able to further the exploration of my topic. The experience was invaluable, as my time in the archives significantly reshaped the structure of my paper.

My visit to the United Nations Archives was an exceptional experience. The archives are located in a separate office building, distinct from the main United Nations headquarters. Walking down a smaller side street to access the building added a certain element of secrecy around the whole process. While conducting research, I had the privilege of working alongside scholars from the University of Connecticut, the University of Wisconsin, and the Oxford University. Being in such close proximity to these doctoral candidates and professors as a University of Florida undergraduate was a remarkable opportunity made possible through the center’s support.

The archive room itself was modest, with just six desks, but the walls were filled with posters illustrating the United Nations’ founding history. Given my research focus on the institution’s early years, it provided a fitting backdrop and a constant reminder of the organization’s rich history. In this setting, I read through folder after folder of documents related to the establishment of international bioethical standards.

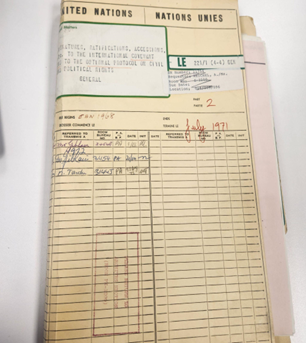

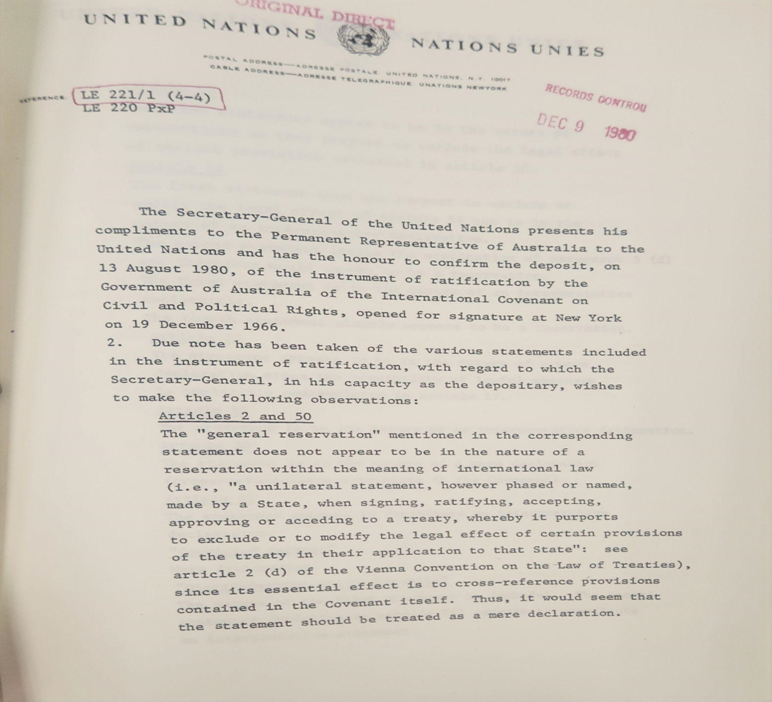

During my research, my project evolved to place greater emphasis on the establishment of the ICCPR as the first instance of enforceable bioethical standards on a global scale. Many of the documents I reviewed consisted of notification letters from various national delegations regarding their signature and eventual ratification of the ICCPR. These documents will be invaluable as I write my next chapter, which examines the role of international bodies in shaping global bioethical principles as demonstrated with the ICCPR.

Among key documents was one in which Australia’s delegation outlined, article by article, its concerns with the ICCPR. Many of these concerns stemmed from fears of infringement on national sovereignty by international organizations such as the United Nations. Although my paper primarily focuses on the United States, documents like this provide a broader understanding of the international debate surrounding bioethics. Despite the atrocities of World War II underscoring the inadequacy of domestic bioethical standards, significant disagreements about the United Nations’ role persisted well beyond the immediate postwar years.

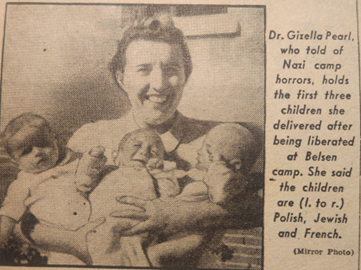

In addition to my time at the United Nations Archives, I conducted research at the New York Public Library Archives. My primary objective was to explore the life of Dr. Gisela Perl, a prisoner physician responsible for the care of female inmates at Auschwitz. While much research has been conducted on the Nazi perpetrators of medical crimes, there has been relatively little discussion on the ethical dilemmas faced by prisoner physicians who endured their own suffering under the regime. My goal was to further detail Dr. Perl’s life in order to add a more personal and human element to my paper through the lens of a Holocaust survivor.

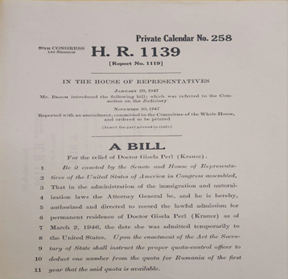

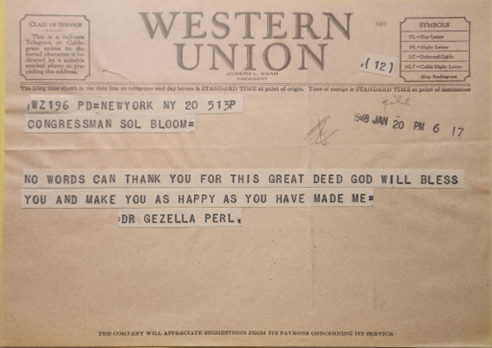

During my time at the NYPL Archives, I gained insight into Dr. Perl’s journey to the United States and the process of obtaining her citizenship. Her residency in the U.S. was facilitated by a special bill introduced by Representative Sol Bloom (19th and 20th New York Congressional Districts) and supported by Eleanor Roosevelt. Dr. Perl’s path to citizenship highlights the significant influence of the Jewish diaspora in shaping postwar political decisions.

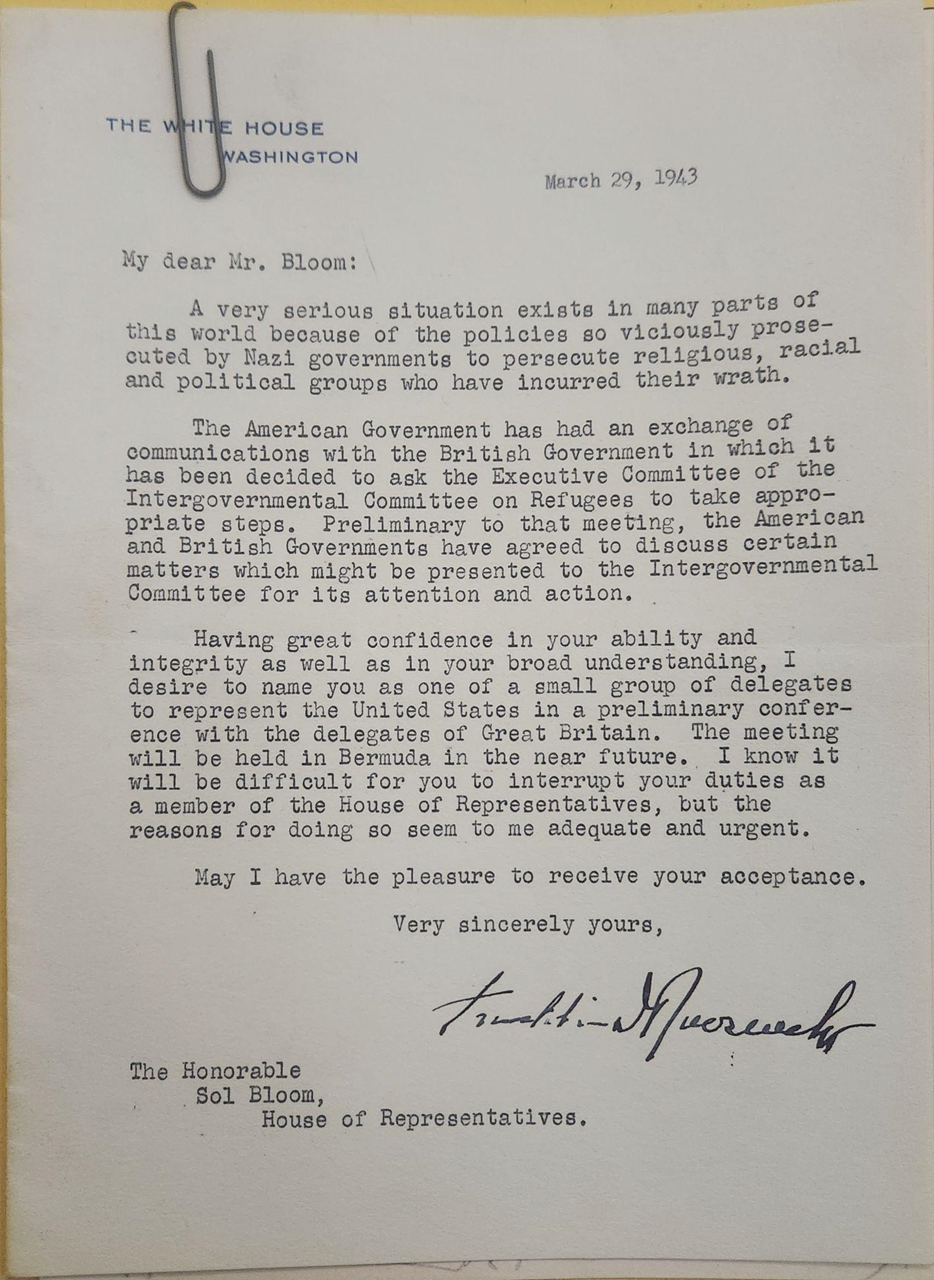

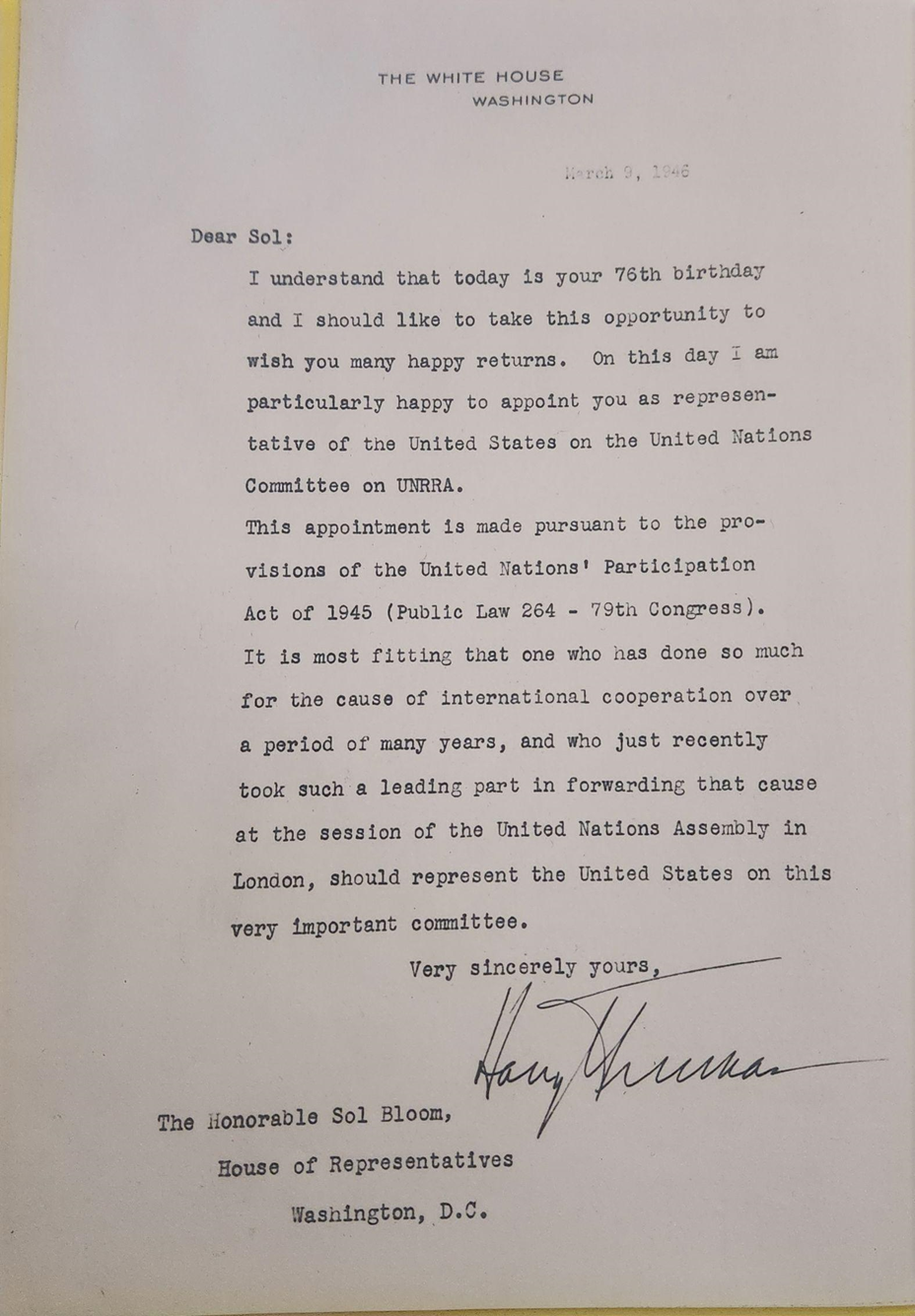

Representative Bloom’s diligent work with displaced persons drew the attention of both President Roosevelt and President Truman. Under President Roosevelt, Congressman Bloom served as an American delegate at the Bermuda Conference of 1943, where the Allies discussed the fate of Jewish refugees in Europe. Later, under President Truman, he was involved with the United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration. These roles, while not directly related to medical crimes, illustrate how testimonies from Holocaust survivors like Dr. Perl contributed to shaping U.S. policy in the postwar world. Further, these documents support the conclusion that key political leaders such as President Roosevelt and President Truman were choosing representatives that were informed on the Holocaust when the time came to select the delegations for committees dealing with medical ethics.

Ultimately, my time at the United Nations Archives and the New York Public Library Archives proved crucial to the development of my honors thesis. Before this research trip, my chapters lacked a common thread to support the paper’s cohesion. The insights I gained during this trip allowed me to refine my study by connecting influential figures such as Sol Bloom and Dr. Perl to my overall discussion on bioethics. These findings have helped me reframe my thesis with a more human-centered perspective. I am deeply grateful to the Jewish Studies Center and the Gary Gerson Scholarship for making this research opportunity possible.

Bibliography:

- Perl, Gisela. Telegram to Rep. Sol Bloom. January 20, 1948. Sol Bloom Papers, New York Public Library Archives, New York, NY.

- Roosevelt, Eleanor. Letter to Sol Bloom. January 29, 1948. Box 56, Sol Bloom Papers, New York Public Library Archives, New York, NY.

- Roosevelt, Franklin D. Letter to Sol Bloom. March 29, 1943. Box 60, Sol Bloom Papers, New York Public Library Archives, New York, NY.

- Truman, Harry. Letter to Sol Bloom. March 9, 1946. Box 60, Sol Bloom Papers, New York Public Library Archives, New York, NY.

- United Nations Archives. Kurt Waldheim to Australian Delegation. “Response to Australian Reservations on the ICCPR.” September 12, 1980. Box: Signatures, Ratifications, Accessions, etc. to the International Covenant and to the Optional Protocol on Civil and Political Rights (General). Folder: LE 222/1 (4-4) Gen Part 4, Jan. 1979 to May 1982. New York, NY.

- Daily Mirror. “Tells of Saving Mothers in Nazi Death Camp.” Associated Press, April 11, 1946, 20. Box 56, Sol Bloom Papers, New York Public Library Archives, New York, NY.

- H.R. 1139, Special Bill to Grant Dr. Perl Citizenship. Box 57, Sol Bloom Papers, New York Public Library Archives, New York, NY.